Upregulating Neurological Control of the Mind-Body: A Conceptual Model

Underlying Observations:

This model is based upon the following observations:

-

Body and mind comprise an integrated system requiring an integrated approach to the problem of human condition,

-

The brain is the controller of all life processes working through the body-mind system,

-

The brain exercises its control by responding to every sensory input it receives whether the input originates from within the body-mind complex or outside in the external world,

-

In general, an autonomic input in the unconscious or subconscious domain generates an autonomic response while only an input in the conscious domain can elicit a conscious response,

-

As any controller, the brain can be overwhelmed by the demands of the processes it controls,

-

Human brain is structured to permit self-regulation of the control demands of the mind-body processes consisting of three mutually dependent types:

-

Autonomic life support processes in the unconscious domain running 24/7,

-

Life related mental processes in the sub-conscious domain such as worry, anxiety, fear, phobias, complexes, likes, wants, dislikes, cravings, longings, habits, addictions, aversions, hatreds, etc. that creep up on us 24/7 minus periods, such as of deep sleep and one-pointed focus, which continually keep getting rarer and briefer, and

-

Activities in the conscious domain arising out of conscious life involvement during waking state.

-

-

Mind is capable of entertaining only one conscious activity at a time,

-

Sub-conscious can move into the conscious and become volitional when our will connects with it,

-

Sub-conscious processes permit conscious control only when they move into consciousness,

-

Control demands of the sub-conscious and unconscious domains may be lumped together in an ‘inner autonomous’ group as they generally increase and decrease together with the exception of the digestion system the demands of which decrease when those of others increase and vice versa,

-

High inner autonomic demands can only accommodate low volitional commitments without overloading the nervous system,

-

Of the autonomic life support processes running 24/7, only breathing lends itself to conscious control,

-

Volume of the inner autonomous demands is much higher than that of the volitional ones,

-

Although the autonomous inner demands do not ordinarily lend themselves to conscious control, their volume makes it incumbent on us to limit their volume to prevent overwhelming the brain,

-

Autonomous demands are handled by the fast acting limbic part of the brain while the volitional ones by the slow acting neo-cortex,

-

High activity of the limbic brain results in high activity of the sympathetic division of the autonomic nervous system in relation to that of the parasympathetic division,

-

An imbalance in the activity of the sympathetic division of the autonomous nervous system over the parasympathetic overloads the brain and adversely affects the immune system,

-

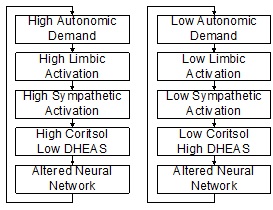

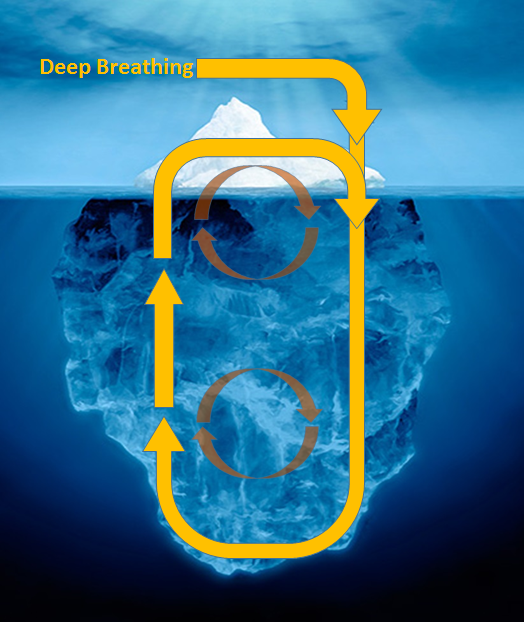

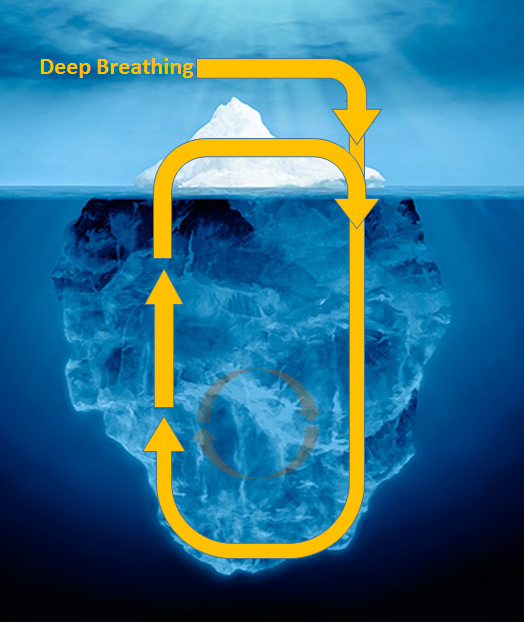

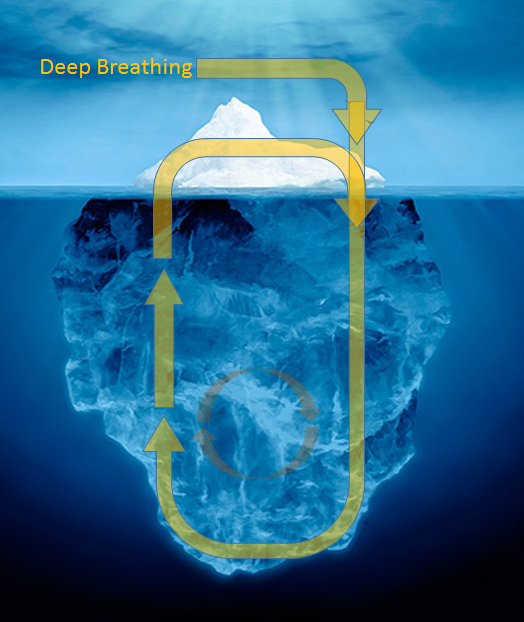

Repeated overloading of the brain sets in motion a run-away cycle (Figure 1) of adjusting the hormonal mix to rewire the brain to meet higher and higher demands,

|

Figure 1: The diagram on the left shows how high inner demand generated by the unconscious and sub-conscious body-mind processes positions the brain to be revved up for meeting continued high demands. On the other hand, the diagram on the right shows how such demands lowered by the practice of conscious deep breathing or one pointed focus on a chosen subject results in predisposing the brain for meeting low demands. It is easier to engage in predominantly physical deep breathing then engaging the mind in one pointed focus. |

-

The brain restructured to meet continuously high demands deals with all inputs, whether of the autonomic or volitional nature, at high speeds stressing the body-mind beyond its coping capacity,

-

Continuously stressed body-mind leads to poor physical and mental health, bad behaviour and poor intellectual and learning abilities with consequential social and economic repercussions,

-

The original disposition of our body-mind depends upon the neurological structure of the brain at birth inherited genetically from the parents and environmentally from the time of conception onwards,

-

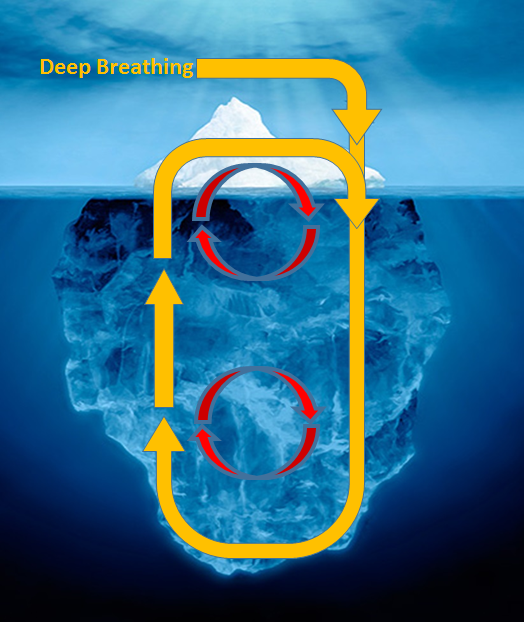

Upregulation of the neurological control of life processes begins with a conscious reduction of the inner autonomous demands of the body-mind using breath as their only available handle,

-

Regulating respiration is noted to regulate all inner autonomous processes of the body-mind affecting our conscious disposition,

-

Volitionally slowing the rate of breathing increases the activity of the parasympathetic division of the autonomic over that of the sympathetic reversing the reactive disposition of the brain caused by the high activity of the sympathetic division of the autonomic over that of the parasympathetic,

-

High activity of the sympathetic division of the autonomic over that of the parasympathetic makes for quick, reflexive, reactive and unconsidered response for all stimuli including those originating from the external world, and

-

Conscious regulation of the inner autonomic demands also modulates those originating consciously in our own volition.

-

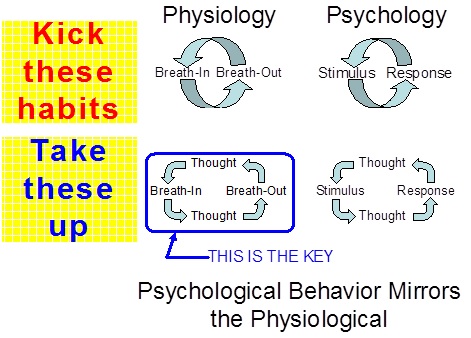

Figure 2 diagrammatically shows the practical application of the conceptual model.

|

Figure 2: Graphical depiction of the practical application of the conceptual model for self-regulating neurological control of the mind-body complex for health, wellness, learning and intellectual ability. |

Self-Regulation and Personality Types

If we quantify control demands broadly as high and low, we can have four possible combinations of the two groups of them. Each of the four combinations broadly defines a personality type into which we can move with the subject self-regulation. In this regard, we must keep in mind that individuals in the same class can be markedly different from each other.

-

Low Autonomic and Low Volitional: We may be born with this kind of disposition or somehow develop it later. Individuals with this dispensation lack any significant ambition. Laziness and sloth set in and life becomes listless and self-centered without significant volitional involvement with others and the environment. Self- centeredness prevents human connection with others in the environment. Slow deep and diaphragmatic breathing for a few minutes a day can open the thought process to the higher perception of mutual connections and dependence.

-

High Autonomic and Low Volitional: This combination is the most common human condition. Inner autonomous demands keep us aroused to an extent that there is little physical energy, psychic energy or clarity of thought left for successful life involvement. Our brains react primarily instinctively or reactively rather than respond with consideration. Expectations are generally unmet making us frustrated, unhappy, and unhealthy. The most direct way to help this human condition is to engage in slow deep and diaphragmatic breathing for a few minutes every day to develop the habit of slow and rhythmic breathing. Once such a habit is established, one can respond to the volitional demands more effectively.

-

Low Autonomic and High Volitional: This is the most desirable combination typical of high achievers. Such human beings generally are calm and considerate. They live in the moment without being bothered by the sub-conscious mind. The result if efficiency and success in whatever they undertake. Brazenness and carelessness can follow in the wake of success if care is not exercised with preventive measures. One needs to keep practicing deep breathing as a measure to prevent the lapse into the less desirable combination of autonomic and the volitional.

-

High Autonomic and High Volitional: This is the least desirable and highest risk combination. It is unsustainable as it is most likely to keep the brain revved up overloading the nervous system. Life is taken over by limbic control to the virtual elimination of the intellectual function of the neo-cortex.