|

"Ideas we don't know we have, have us". Psychologist James Hillman |

|

"Wholeness -- a state in which consciousness and the unconscious work together in harmony." Psychologist Daryl Sharp |

|

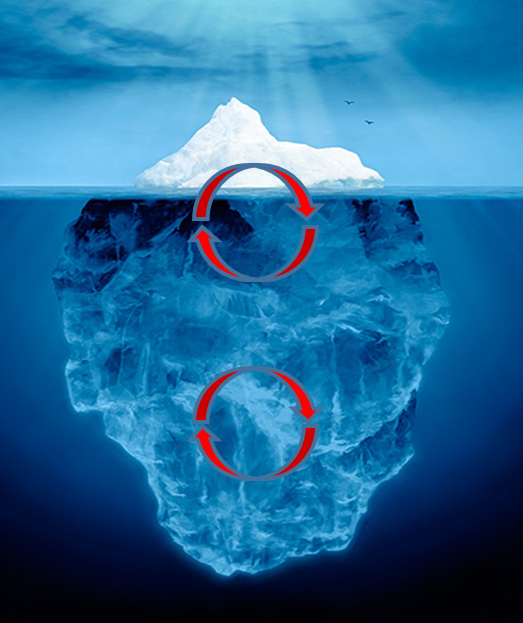

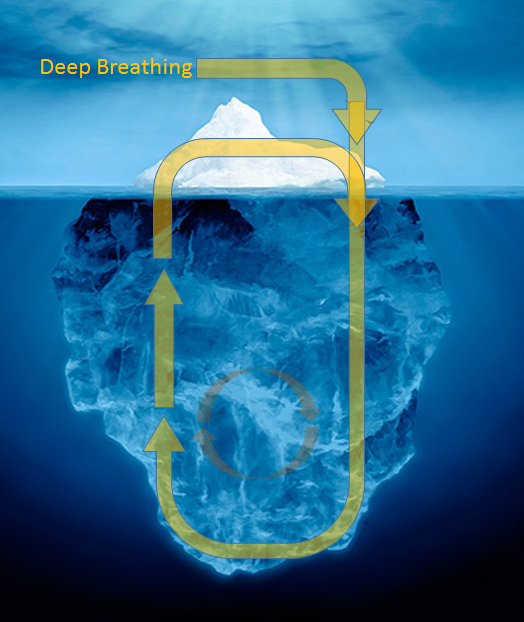

Figure-1 shows human mind as an iceberg which psychology aptly uses as a metaphor for it. The iceberg floats in the ocean with only a small part visible above the surface with the rest partially visible or invisible below it. The visible part above the surface of the ocean represents the conscious part of mind. The part partially visible immediately below the surface represents the sub-conscious part and the totally invisible bottom part of the iceberg deep below the surface represents the unconscious part of mind.Two sets of red arrows in red represent interactivity back and forth between two pairs of adjoining contents of mind. |

Content of human mind exists in three interacting parts: conscious, subconscious and unconscious. Only a small part of it is conscious with the rest divided into subconscious and unconscious. Parts of the subconscious content randomly move into conscious and conscious content moves into subconscious domain. Similarly parts of the unconscious move into subconsciopus and vice versa.

As noted above, ordinarily in waking and dreaming states there is a degree of ongoing interactivity between the conscious and the subconscious, and the subconscious and the unconsciousness parts of mind. Some content of the conscious moves into the subconscious and that of the subconscious into the conscious. Similarly, some content of the subconscious keeps moving into the unconscious and that of the unconscious into the subconscious. We cannot excercise any control on this interactivity. Anything can pop into and out of our consciousness randomly at any given time making it difficult to pay attention to a specific subject for a significant amount of time. For this reason, mind is compared with a monkey that keeps jumping incessantly from one branch to another.

Whatever happens in our bodies or whatever we do in the external world begins with a conscious or subconscious perception in the mind. Our mind is the controller of our bodies and our behaviour in life. Brain is its physiological correlate. All controllers including our brains work with a feedback loop. When the controller perceives the need to do something, it does that in response to the perception and when it perceives that it has done enough of it, it stops.

A unit of perception is called a stimulus. We must do something in response to it. We may react or respond. We simply are built in that way, there must be a reaction or a response to acknowledge every stimulus whether it is in conscious or subconscious domain. Sensory nerves transmit the stimulus to the brain and motor nerves transmit our reaction or response to the appropriate parts of the body to acknowledge it. If the stimulus is subconscious, our reaction is also subconscious and immediate: without any conscious consideration or thought. If the stimulus is in conscious domain, we may react subconsciously or respond with conscious consideration. The term reaction is used to indicate subconscious activity and response for the conscious.

Various body functions such as beating of the heart, breathing, metabolism, etc. run 24/7 to sustain life. All of them must work autonomously or unconsciously all the time we are alive. They generally do not lend themselves to conscious control. The only exception to this rule is breathing which ordinarily runs unconsciously but can be run under our conscious control.

Heart pulsation is a typical example of a body function which works only in an autonomous or unconscious manner. When our brains receive a subconscious signal about the availability of oxygenated blood to be pumped, it reacts subconsciously in sending a motor signal to the heart muscle to pulse. All the cardiac pulsations happen autonomously without the possibility of our direct and conscious interference.

On the other hand, consider breathing; when the brain receives a subconscious signal through the sensory nerves about inadequate oxygen and excessive carbon dioxide in the lungs, it is a stimulus for it to subconsciously react with a motor signal for the lungs and associated muscles to breathe out. When the brain subconsciously perceives that the lungs do not have enough air in them, we subconsciously react to it by breathing in. When we decide to run the breathing function consciously, the stimuli to breathe in and to breathe out are in conscious domain and so are the responses.

We just examined physical survival related activities of our mind within; let us now look at life in the external world and related mental processes. We spend much of our time dealing with subconscious feelings broadly classified as (1) likes, wants, desires, cravings, longings, habits, addictions, etc., (2) dislikes, aversions, hatreds, etc., (3) fears, worry, anxiety, phobias, obsessions and the like, and (4) complexes, feelings of finitude, helplessness and inadequaccies, depression, anger etc. These subconscious feelings seem never to leave us alone as they creep up on us almost 24/7. In addition, we need to look after involvements in the conscious domain during waking states. These involvements include business, professions, duties that we take on ourselves, school, learning, leisure, sports, family pursuits etc.

Thus, our mind true to its metaphor of the iceberg spends most of its energy in dealing with the unconscious and the subconscious pursuits which because of the immediacy, urgency and unpredictability of its nature takes precedence over the conscious pursuits which to an extent are subject to planning and procrastination.

Which kind of pursuits should we prefer to engage in for full, healthy, successful and meaningful life? The obvious answer to this question is that we should attend to the conscious ones. Will that work?

The answer to this question becomes obvious if we ask this question, "What kind of stimuli then are critical for full, healthy, successful and meaningful life?" Isn't it obvious that we should first manage the unconscious, then the subconscious and finally attend to the conscious if we want to ensure success? Failing to do so is risking confrontation with the interests of the unconscious and the subconscious parts of the mind represented by the submerged part of the glacier which is humongous in comparison with the visible part representing the conscious. Submerged glaciers are known to be responsible for many a shipwreck.

|

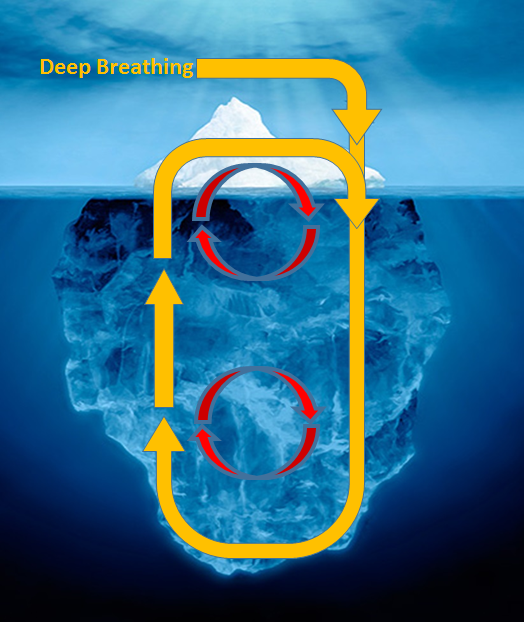

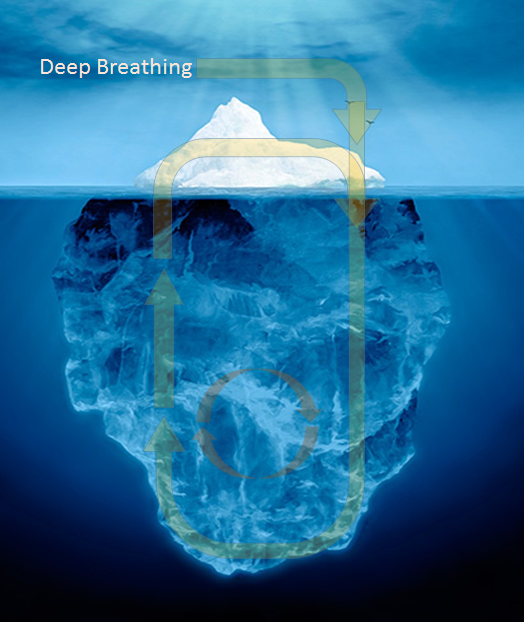

Figure-2 shows stage 1 of deliberate deep breathing which adds another channel of interactivity, shown in gold, from the conscious to the unconscious, from the unconscious to the subconscious and then back to the conscious. This channel tends to replace the interactivity of the ordinary mind shown in red. |

Ordinarily breathing is an autonomic process running 24/7 in the control of our unconscious mind in accordance with our emotional state of which we hardly are aware. Deliberate deep diaphragmatic breathing run by our conscious mind puts it in control of the unconscious. The unconscious mind under the influence of the conscious interacts with the subconscious mind which so influenced then interacts with the conscious preventing random thoughts of the subconscious from popping into consciousness. Figure 2 shows this channel of interactivity superimposed by deep breathing in gold. This initially superimposed channel gradually replaces the ordinary channel of interactivity.

|

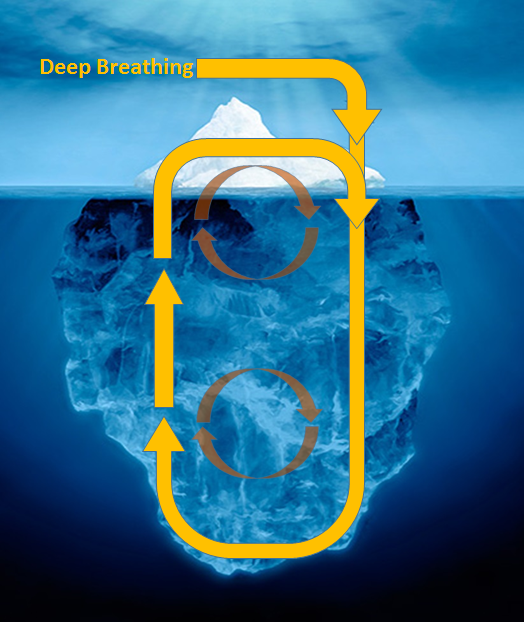

Figure-3 shows stage 2 of the practice of deep breathing. Notice how the channel of mental interactivity imposed by deliberate deep breathing gradually becomes the dominant channel reducing the extent of the ordinary channel shown by two sets of arrows. The reduction in the intensity of the color of these arrows from Figure-2 to Figure-3 is intended to indicate this reduction. |

The reduction or elimination of stray thoughts from conscious mind reduces or eliminates related nervous traffic calming the nervous system. Calmer nerves help us to pay attention and think in a focused way to learn, solve our life problems and adjust our behaviour in the community and family in addition to prevent physical and mental disorders.

|

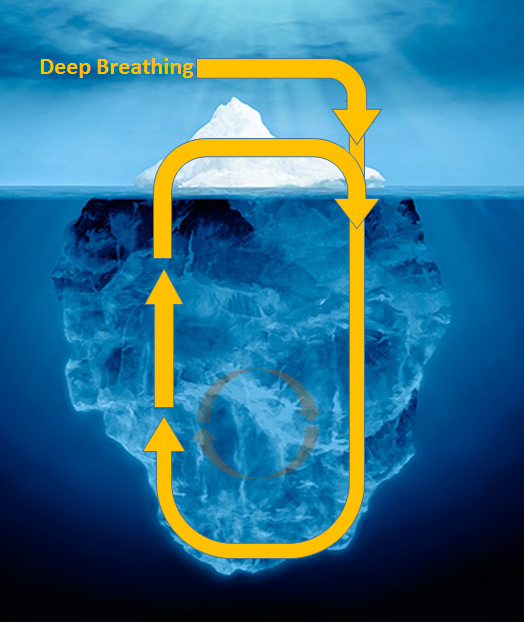

Figure-4 shows stage 3 of deep breathing. Notice complete elimination of one set of arrows of ordinary mental interactivity and a significant dimming of the other. At this stage of the practice of deep breathing, random consciousness of the subconscious is totally eliminated. |

Regular practice of deep breathing for a few minutes a day over a period of time changes our disposition from reactive to thoughtfulness. In addition, it makes us healthier, happier and in harmony with the family, community and the environment.

|

Figure-5 shows stage 4 of deep breathing. Notice how we can sustain the elimination of random popping into consciousness of the content of the subconscious mind with reduced mental and physical effort of deep breathing. |

Regular practice of deep breathing is a self management tool the use of which up regulates our control system for health, happiness and oneness.

|

Figure-6 shows stage 5 of deep breathing. Notice how we can sustain the elimination of random popping into consciousness of the content of the subconscious mind with even further reduced mental and physical effort of deep breathing. At this stage, deep breathing is well established as a habit. |

|

Figure-7 shows the ultimate achievable with the practice of deep breathing. This presents an ideal for which to strive. There is no effort of deep breathing and no content of the conscious mind. Here one just is in the realization that it is not just brain or mind that runs the process of breathing that keeps us alive. That something, although unseen, is the real animator of me, you and the whole universe. |